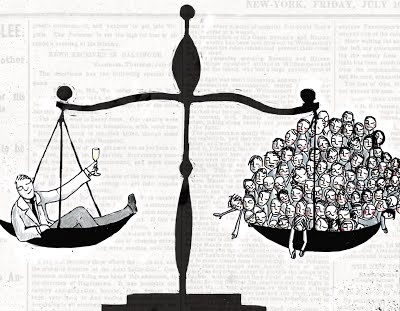

A startling picture of global inequality has been presented by Oxfam in a new report which finds that just 62 billionaires control as much wealth as ‘the bottom half of humanity’; a staggering 3.6 billion people. In a trend pointing to accelerating economic polarisation, the one percent (62 people) has increased its wealth by a massive 44 percent since 2010 while the collective wealth of the bottom 50 percent dropped by a near identical 41 percent or $1 trillion. This is largely due to a stagnation of incomes among the bottom half of the world’s people who have received a paltry one percent of the total increase in global wealth since 2000. According to Oxfam, these trends point to a world ‘with levels of inequality we may not have seen for over a century’ and cast serious doubt on the outcomes of the 15 year international effort to cut global poverty by half; the Millennium Development Goals. With the United Nations’ agreement last September on another 15 year development process to 2030 comprising 17 Sustainable Development Goal s (SDGs) backed up by 169 targets, development practitioners everywhere should seriously reflect on the SDGs’ capacity to ‘end poverty in all its forms everywhere’.

A London-based non-governmental organisation (NGO), Share The World’s Resources, believes that the SDGs are not equal to the key challenges confronting countries in the global South. For example, the goals have been shorn of any acknowledgement or analysis of the historical (colonialism, structural adjustment programmes) or contemporary (neoliberalism, privatisation of public services) causes of inequality essential to the formulation of requisite action and redress. The SDGs also appear toothless to reverse the growing trend of financial flows from global South to the global North completely eclipsing aid and investment in the developing countries by Northern governments and institutions .

Crippling debt

More than 40 years on from the origins of the debt crisis in low and medium income countries, the Jubilee Debt Campaign estimates the total global debt owed by debtor countries to be $13.8 trillion. One of the architects of the global debt crisis, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), has flourished in the economic chaos that has accompanied the global financial crisis of 2008. It continues to implement devastating structural adjustment programmes (SAPs) as a price for extending loans to toiling economies. SAPs require that debtor countries reduce spending in crucial social areas of government expenditure such as health and education which in turn results in lower standards of living. There is no provision in the SDGs for debt restructuring or cancelation which means that this major drain of resources from the global South will continue unabated.

Similarly, the SDGs are ill-equipped to deal with the lost revenue to developing countries caused by illicit financial flows calculated in 2012 at $991 billion. This capital is lost to the global South through crime, corruption and tax evasion, and has been described by Global Financial Integrity (GFI), a US-based research organisation, as ‘the most damaging economic problem plaguing the world’s developing and emerging economies’. Raymond Baker, Chair of GFI, said ‘These outflows—already greater than the combined sum of all FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) and ODA (Overseas Development Aid) flowing into these countries—are sapping roughly a trillion dollars per year from the world’s poor and middle-income economies’. The SDGs have not created an international tax body to clamp down on evaders and close legal loopholes that allow wealthy individuals and corporations to play a pittance in tax. The IMF, no less, has suggested that developing countries lose $200 billion in corporate tax avoidance every year. Putting this figure in context, Angel Gurría, the secretary-general of the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) ‘reckons that developing countries lose three times more to tax havens than they receive in international aid each year’.

Aid in context

In a rounded analysis of the financial problems blighting the economies of low income countries, aid is arguably well down the policy pecking order. In 2012, remittances – the transfer of money home by migrants working abroad – amounted to $530 billion, ‘more than three times larger than total global aid budgets’. Illegal capital outflows were eleven times greater than ODA in 2012 and, according to Share The World’s Resources (STWR), governments in low- and middle-income countries are indebted to the tune of over $4 trillion dollars, and spend more than $1.4 billion every day repaying these debts. ‘On average’, states STWR, ‘developing countries are returning over 400% more in debt service repayments than they receive in aid’. The SDGs lack any actionable, timebound pledges for financing development but in any event, as we have seen, aid is not the answer to the fundamental weaknesses in low income economies. However, we repeatedly find the international development sector in Ireland and in many other European states, elevating aid to the top of its policy agenda. We had the ‘Act Now on 2015’ campaign in Ireland that sought to have the government comply with the (45 year old) target of raising the aid budget to 0.7 percent of national income.

The campaign failed to reach its goal as the aid budget was cut in six consecutive years after the 2008 financial crisis. It is estimated that Ireland’s ODA in 2016 will represent 0.36% of GNP representing a modest increase of €40 million on 2015 and still well short of the 0.7 percent target. But perhaps the bigger issue is whether the sector’s continued focus on aid is the best way to support countries in the global South. Simply falling in behind the SDG agenda and pressing for increases in aid will not alter the social and economic trends picked up by Oxfam’s report. After 15 years of MDG delivery, The Rules, a global network of activists, estimates that 4.1 billion people are living in poverty on less than $5 a day; that represents 60 percent of the world’s population.

The elephant in the room

In its preoccupation with aid and the SDGs, the sector is in danger of losing sight of the elephant in the room when we debate the causes of poverty in the global North and South; the market fundamentalism of neoliberalism. This economic model which believes in the primacy of markets to deliver services and seeks to reduce the role of government in public life has overseen a ‘race to the bottom’ as vital services essential to the welfare and protection of citizens have been hollowed out by market reforms. The leverage afforded it by the financial crisis has enabled the IMF to extend the implementation of structural adjustment reforms into the global North, including Ireland. Following waves of austerity implemented post-2008, Ireland has 750,000 people living in poverty, an increase of 55,000 since 2011. 230,000 children live in poverty, including an increase of 12,000 in one year despite protestations of an economic recovery. There are also 94,700 working people living in poverty which points to stagnating incomes for those on low wages. Perhaps the biggest failing of the SDGs, therefore, is that there is no deviation from the neoliberal growth model which has created many of the problems they seek to address. If the goals aim to raise living standards through growth on a global scale how can they possibly hope to limit the warming of the earth’s planet to two degrees Celsius , a fundamental plank of the COP 21 climate change conference in Paris in December 2015?

At this pivotal juncture for the sustainability of the planet and the welfare of its citizens, the development non-governmental sector needs to change direction away from a rigid adherence to aid policy formulation and begin debating the real issues that matter to the global South; stopping illicit financial flows, removing obstacles to remittances, closing tax havens and loopholes facilitating evasion, and ensuring debt cancelation for low income countries. The sector also needs to explore and share alternatives to neoliberalism drawing upon examples at community and national level, particularly in Latin America where development processes have been informed by social need rather than serving the needs of the market. As Oxfam suggests ‘it is time to reject this broken economic model’ and ‘do something about it’.