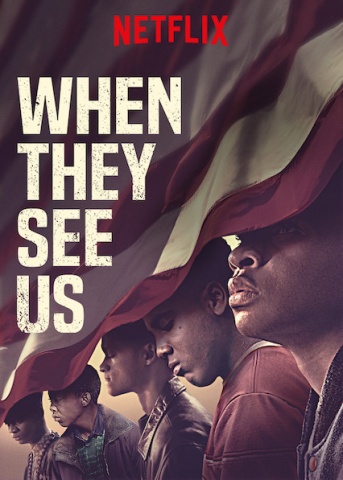

On 19 April 1989, a 28 year-old investment banker, Trisha Meili, went for her regular jog in Central Park at 9.00pm. In the course of her run, she was hit over the head, dragged 300 feet, viciously raped and beaten, and left for dead by her assailant. At the same time, around 30 Black and Latino teenagers streamed into the park from East Harlem, five of whom were arrested for the assault on Trisha Meili who, at the time, seemed likely to succumb to her injuries. What followed has become a national scandal; a miscarriage of justice that revealed the New York Police Department and District Attorney’s Office to be guilty of racial profiling and a fundamental disregard for legal and human rights. The five boys - Raymond Santana (14), Kevin Richardson (14), Antron McCray (15), Yusef Salaam (15) and Korey Wise (16) - were catapulted into a nightmarish and brutalising experience at the hands of racist police officers orchestrated by Lead Prosecutor, Linda Fairstein. Rather than prosecuting suspects on the basis of physical evidence, Fairstein immediately decided on the boys’ guilt and worked from that premise to secure their convictions at any cost. The arrest, trials, incarceration and, ultimate, exoneration of the five has been recreated in a gripping four-part television drama, When They See Us, directed by Ava DuVernay, who received an Academy Award nomination for Selma (2014) and went on to make 13th (2016), a documentary about the United States’ (US) judicial system and what it tells us about racial inequality.

Trump and the death penalty

DuVernay seems assured of more awards and recognition for When They See Us (2019) which has become event television; a series which has risen above its medium to capture a national mood of anger and unease at the state of race relations in Trump’s America thirty years on from the 1989 travesty of justice. In fact, When They See Us is a drama in which Donald Trump prominently features because in 1989, he spent $85,000 on full page advertisements in the four main newspapers in New York calling for the restoration of the death penalty. The ad said ‘I want to hate these muggers and murderers. They should be forced to suffer and when they kill, they should be executed for their crimes’. The headline of the advertisement screams in upper case ‘BRING BACK THE DEATH PENALTY. BRING BACK OUR POLICE’. Michael Warren, who was a member of the legal team for the five boys, believes that Trump ‘poisoned the minds of many people who lived in New York and who, rightfully, had a natural affinity for the victim’. He believed that the jurors ‘had to be affected by the inflammatory rhetoric in the ads’.

Despite the fact that the boys were exonerated of any involvement in the Central Park attack in 2002, Trump remains unrepentant saying this month ‘You have both sides of that. They admitted their guilt’, adding that ‘If you look at Linda Fairstein and if you look at some of the prosecutors, they think that the city never should have settled that case’. His remarks carry a queasy relation to the moral equivocation drawn by Trump between neo-Nazis and members of the Klu Klux Klan and anti-racist protestors at a demonstration in Charlottesville in 2017. Trump blamed ‘both sides’ for violence at the protests despite one of the White Supremacists, James Alex Fields Jr, ramming a car into a crowd of activists killing a woman, Heather Heyer. Trump’s moral ambiguity when it comes to race crime has spanned the three decades since the Central Park case and prompted The New York Times to opine that ‘Donald Trump is a racist. He talks about and treats people differently based on their race. He has done so for years, and he is still doing so’.

Trump’s casual and regular use of racist language in his description of migrants, Muslims, Latinos and Blacks is one of the reasons why When They See Us has touched a nerve in America where police violence against the Black community has been condemned in a new report by The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR). The report finds that racial disparities ‘permeate the criminal justice system, are widespread and represent a clear threat to the human rights of African Americans, including the rights to life, personal integrity, non-discrimination, and due process, among others’. The report also considers:

“that issues of discrimination in policing and criminal justice in the U.S. are inseparable from social stigma and hate speech; violence by private citizens; an enduring situation of racialized poverty; and intersectional discrimination; as all of these are also governed by a structural situation of discrimination and racism”.

A miscarriage of justice

Many of these concerns are evident in When They See Us which begins with the arbitrary arrest of the five teenage boys who are aggressively questioned by police officers without their parents present for hours on end without food or a toilet break. The boys are coerced into signing confessions and their interviews are filmed for use in their subsequent trials. These scenes are gruelling to watch and shot in tight, confined spaces that add to the suffocating pressure we see put on the boys to confess. Physical and oral abuse is heaped on the five leaving them disoriented, frightened and vulnerable to the demands of the police. Indeed, such is the level of police aggression that one of the parents, Bobby McCray, fearful for the life of his son, compels him to confess. Another parent, Sharon Salaam, manages to secure the release of her son, Yusef, but he is not spared from the injustice that follows.

Episode two focuses on the trials of the boys in which the defence attorneys make clear the lack of physical evidence and DNA connecting them to the crime. Such are the inconsistencies in the only evidence presented by the prosecution – the coerced confessions – that Fairstein insists on two trials to prevent the disjointed and contradictory nature of the filmed confessions becoming completely revealed. Fairstein’s certainty of the boys’ guilt brooks no doubt and sweeps away the reservations of Prosecuting Attorney Elizabeth Lederer. Despite the lack of physical evidence connecting any of the boys to the crime, they are found guilty in both trials and convicted to severe sentences ranging from five to fifteen years. One of the boys, Korey Wise was tried and sentenced as an adult and served thirteen years in adult prisons. The four other boys served 6–7 years in juvenile facilities.

The third episode follows the lives of Kevin, Yusef, Antron and Raymond after their release as they struggle to adjust to difficult domestic lives that are heavily constrained by curfews imposed on them as convicted sex offenders and former convicts. Only the most menial jobs are open to them despite Kevin, Raymond and Yusef completing degree courses in prison. Raymond ultimately goes back to prison for drug dealing while the other three men manage to survive in an unforgiving society. The drama is excellent in portraying how the men continued to serve their sentences outside prison, denied the kind of opportunities and liberties we all take for granted.

Prison and exoneration

The fourth and, perhaps best episode, is given over in its entirety to the thirteen years served by Korey Wise in the adult penal system. Sentenced as an adult at the age of 16, Wise was shunted around different prisons, often long distances from his home in New York, which made family visits extremely difficult. The series makes it plain that the sentences of the boys were shared by their families who, in some cases, found themselves ostracised by association with their alleged guilt or unable to bear the financial cost of prison visits. Two sets of actors – all superb – play the five as adolescents and adults – with the exception of Jharrel Jerome, who plays Korey Wise in all four episodes. He convincingly transitions Korey from a terrified teenager initially incarcerated in Riker’s Island, to a young adult navigating the complex prison regime, both official and unofficial.

This episode helps us understand the interior life inside prison as Korey’s mind wanders and replays different scenarios to those that led to his arrest. He wasn’t one of the original police suspects and became caught up in the maelstrom after lending support to a friend. He spends long periods in solitary at his own request for his own protection having been beaten by fellow inmates to within an inch of his life. We learn that sex offenders are only one step up from child molesters and reviled in the prison system. Then in 2002, a prison inmate, Matias Reyes, confessed to the attack on Trisha Meili and his DNA matched that found at the scene. The five men were exonerated of the crime but not before Linda Fairstein and the police tried to suggest that Reyes was a sixth man, who had attacked Meili in league with the five. However, Reyes made clear that he was the sole assailant and in 2014 the city of New York reached a settlement with the five worth $41 million.

Coerced confessions unsafe

Some viewers of When They See Us, may feel that a four-part drama spanning five hours, somewhat truncates the stories of the five. For example, we see very little of the time spent by four of the boys in juvenile facilities or learn much about their lives before the Central Park case. Nonetheless, the structure feels right in providing space for the families to tell their stories and Ava DuVernay explains in a follow-up discussion, When They See Us Now, with the cast and five men, that they all felt it important to devote an entire episode to the story of Korey Wise.

Viewers of the show with memories of the Irish conflict, will immediately recollect the scandalous miscarriages of justice – The Guilford Four, Maguire Seven and Birmingham Six - suffered by mostly Irish citizens in Britain. They were wrongly convicted on the back of police coercion and forced confessions, of pub bombings in Birmingham and London, carried out by the Irish Republican Army in the 1970s. They, too, were exonerated but only after long prison sentences were served and loved ones lost. They remind us that there is no place for police coercion in a properly functioning judicial system. Confessions extracted in such circumstances are unsafe and can lead to horrific miscarriages of justice.

Education is the key

When They See Us reveals a rotten edifice of racism and corruption in the judicial system in New York. We know with the establishment of Black Lives Matter that state and vigilante violence against Black communities is a concern across America. Jane Rosenthal, an executive producer on When They See Us sums up the current situation well when she says:

"Our country has more people of color incarcerated and we have more people overall incarcerated than any country in the world. That right there is wrong. We need to be adjusting our education system. It costs more to house a person in prison than it does to educate. There are still juveniles at Rikers Island and families that can’t post bail. This story could be anybody".

According to Netflix, 23 million account-holders have watch When They See Us, making it one of its most watched-ever shows. This drama has struck a chord in the US and seems to capture the vulnerability of Black communities to what the IACHR called a ‘structural situation of discrimination and racism’. In the uncertain and volatile political environment of Brexit and Trump, active citizenship and education informed by values of respect, diversity, social justice and equality are needed more than ever.

References

Aguilera, J (2019) ‘President Trump Refuses to Apologize for His Central Park Five Ad: “They Admitted Their Guilt”’, Time Magazine, 18 June, available: https://time.com/5609622/trump-central-park-five-apology/ (accessed 29 June 2019).

BBC (2019) ‘Guildford pub bombings inquest to resume 45 years on’, 30 January, available: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-surrey-47057539 (accessed 30 June 2019).

Black Lives Matter (2019) ‘Herstory’, available: https://blacklivesmatter.com/about/herstory/ (accessed 30 June 2019).

Joyner, A (2019) ‘How much was the Central Park Five Settlement? “When They See Us” victims sued New York City for $41m’, Newsweek, 19 June, available: https://www.newsweek.com/central-park-five-settlement-when-they-see-us-41m-1444765 (accessed 30 June 2019).

Laughland, O (2016) ‘Donald Trump and the Central Park Five: the racially charged rise of a demagogue’, The Guardian, 17 February, available: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/feb/17/central-park-five-donald-trump-jogger-rape-case-new-york (accessed 30 June 2019).

Leonhardt, D and Philbrick, I (2018) ‘Donald Trump’s Racism: The Definitive List’, The New York Times, 15 January, available: https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/01/15/opinion/leonhardt-trump-racist.html (accessed 30 June 2019).

Netflix (2019) When They See Us, available: https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/80200549 (accessed 30 June 2019).

Netflix (2019) When They See Us Now, available: https://www.netflix.com/gb/title/81147766 (accessed 30 June 2019).

Nicholson, R (2018) ‘A Great British Injustice: The Maguire Story review – a harrowing tale’, The Guardian, 25 November, available: https://www.theguardian.com/tv-and-radio/2018/nov/25/british-injustice-maguire-story-review-family (accessed 30 June 2019).

Payton, M (2016) ‘Birmingham pub bombings: Who are the Birmingham Six? What happened in the IRA attack? Everything you need to know’, The Independent, 1 June, available: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/birmingham-pub-bombings-1974-ira-who-are-the-birmingham-six-what-happened-in-the-attack-everything-a7059876.html (accessed 30 June 2019).

Ransom, J (2019) ‘Trump Will Not Apologize for Calling for Death Penalty Over Central Park Five’, The New York Times, 18 June, available: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/18/nyregion/central-park-five-trump.html (accessed 29 June).

Riotta, C (2019) ‘James Fields jailed: White supremacist who killed woman during Charlottesville rally sentenced to life in prison’, The Independent, 28 June, available: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/james-fields-jailed-life-prison-white-charlottesville-murder-heather-heyer-a8979986.html (accessed 30 June).

Saulny, S (2002) ‘Convictions and Charges Voided In '89 Central Park Jogger Attack’, New York Times, 20 December, available: https://www.nytimes.com/2002/12/20/nyregion/convictions-and-charges-voided-in-89-central-park-jogger-attack.html (accessed 30 June 2019).

Shear, M and Haberman, M (2017) ‘Trump Defends Initial Remarks on Charlottesville; Again Blames “Both Sides”’, The New York Times, 15 August, available: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/08/15/us/politics/trump-press-conference-charlottesville.html?module=inline (accessed 30 June 2019).

Strause, J (2019) ‘How “When They See Us” Puts Trump in the Hot Seat’, The Hollywood Reporter, 1 June, available: https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/live-feed/they-see-us-team-erasing-central-park-five-moniker-calling-trump-1213035 (accessed 30 June 2019).

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) (2019) ‘IACHR Releases New Report on Police Violence against Afro-descendants in the United States’, 18 March, No 069/19, Washington: The Organisation of American States, available: https://www.oas.org/en/iachr/media_center/PReleases/2019/069.asp (accessed 30 June 2019).

Warner, S (2019) ‘Netflix reveals that over 23 million watched When They See Us - one of its most-watched shows ever’, Digital Spy, 26 June, available: https://www.digitalspy.com/tv/ustv/a28195968/netflix-when-they-see-us-23-million-most-watched-shows-ever/ (accessed 26 June 2019).

Waxman, O (2019) ‘President Trump Played a Key Role in the Central Park Five Case. Here’s the Real History Behind When They See Us’, Time Magazine, 31 May, available: https://time.com/5597843/central-park-five-trump-history/ (accessed 29 June 2019).